It was 98 years ago that the inaugural Ryder Cup took place, writes Ross Biddiscombe, and so 20 June 2025 is an appropriate time to start a series of unique features about the event, because there are now 98 days to go until the 45th match at Bethpage in Farmingdale, New York.

To understand why the match came into being, we need an appreciation of the 1920s, the golfing landscape on both sides of the Atlantic, and particularly the first attempts at an official team golf contest. This knowledge makes clear why Bethpage will deliver the most passionate atmosphere ever for the contest; it’s the latest culmination of an intense rivalry that is profound and comes from a place that is beyond sport.

The 1920s decade was one of massive social and economic change following the end of World War I in 1918. Much of Europe was devastated and Britain was adjusting to having two million men (many in their late teens or early 20s) either killed or wounded during the four-year conflict. This was over 4% of the 46 million population, a lost generation of artists, politicians, factory workers, farmers and, of course, sportsmen.

Post-war economic growth was slow, weighed down by strikes and historically high unemployment; social tensions rose as many elites partied away their sorrows while the working class fought poverty by finding parties of another kind, in the new political world.

Meanwhile, America benefitted from a war they joined in the final 18 months. Although over 310,000 US troops were killed or wounded (0.3% of the near 100 million population), the US economy boomed due to one-way trade to Europe, mostly raw and manufactured goods such as cotton, wheat, brass, rubber and cars.

A power shift was happening which was reflected in every aspect of the two societies, even in golf. The USA was beginning to dominate the new century; the upstart colony was finally emerging from the shadow of its former master.

While Britain seemed to wallow in the past, America looked to the future. Inventions – from the Ford motor vehicle assembly line and traffic lights to the safety razor and the electric blanket – came out of the US and many new ideas came too from a nation obsessed with information and entertainment, radio, newspapers and the movies. Media shaped public opinion and a young nation searched for every reason to prove its new-found dominance. But economic and technological superiority were hard to prove – why not use a sports field where heroes were found. For the average American this was more relatable and more fun.

However, neither the most popular team games in Britain – football, cricket and rugby – nor America’s national game of baseball could provide a fair sporting contest. But golf was ideal. Post-WWI, Britain and the US were the world’s only significant golfing nations and a team match could settle international bragging rights.

Newspaper sports writers – especially in America – viewed a golf match through a social lens; for them, British golfers represented tradition and the Old World while their US counterparts were future rulers of the sport. Britain – where the home of golf was situated – were match favourites and America, who learned the game from immigrant Scots and English, were the scrappy underdogs. It would be a war between two proud and contrasting cultures; the ancient kingdom vs the former colonists. The whole thing read like a movie script.

In addition, golf was taking a different direction in the two nations. A golfing boom in the UK, especially in England, had lasted from the mid-1860s to 1914. Between 1890 and the start of World War I, 1,200 golf clubs were laid out in England alone. But the astonishingly high loss of young British men in The Great War stalled the growth, both in golf course building and participation.

Contrastingly, America’s fascination with golf had been sparked in 1900 by British golf star Harry Vardon’s first barnstorming tour and then it increased in 1913 when 20-year-old amateur US golfer Francis Ouimet won his country’s Open, beating Vardon in the process. Suddenly, thousands of young Americans took to the links.

It was no surprise that American ingenuity helped bring about the first Britain-US team golf contest. Eleven pros – sponsored by the US magazine Golf Illustrated – set off for Britain in 1921, primarily to take part in The Open at St Andrews, but with an idea of a team contest as well. The two PGAs were not sufficiently powerful to stage the match, so the magazine along with the new golf club at Gleneagles in Scotland took the lead. The US golfers would play in three events: the Britain-US team match at Gleneagles; a big money individual tournament (sponsored by the Glasgow Herald newspaper) staged at the same venue; and, finally, The Open.

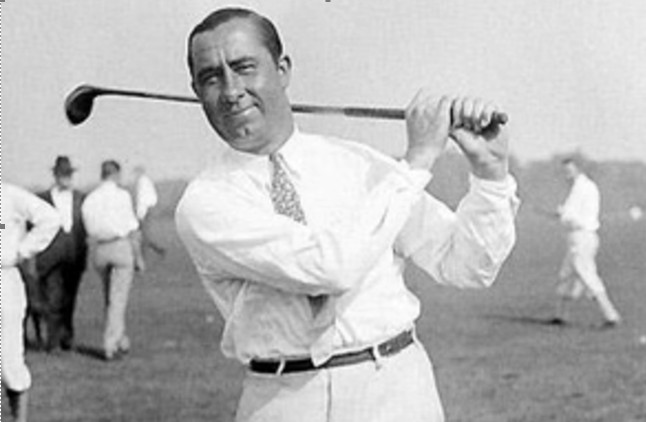

The three outcomes illustrated the equality of talent among the two nations. Sussex-born Abe Mitchell’s victory in the individual tournament won him £250, while America crowned its first ever Open champion, although Jock Hutchison was a Scottish ex-pat born in St Andrews who played under the Stars and Stripes as a recently naturalised US citizen. In addition, two American-born golfers – including Walter Hagen – finished in the top 10.

But it was the International Challenge that now stands out as most significant. It was a 10-man team affair, and the Brits won easily, 9-3 over two competition days consisting of foursomes and singles matches. The US ambassador to Britain travelled to Perthshire for the match and the newspapers waxed lyrical: “Home Team Victorious” roared the Glasgow Herald.

The team result seemed definitively to favour Britain as golf’s foremost nation, especially as four of the Americans were new US citizens, originally born in Scotland (three) and England (one). But look deeper and this defeat would herald the change to come: over half the British team were over 40 (including two in their 50s), while five of the US team were American-born and aged between 22 and 28. There lay a more accurate indication of golf’s future leading nation.

The young Americans licked their wounds and British team of veterans had no trophy to mark their victory in this first international match between golfing professionals. But the contest was an indispensable building block for when a small gold cup was manufactured for a similar contest seven years later. A colossal flame of rivalry had been lit.

Ryder Cup 2025 Series Part 2 will unveil insights into the next unofficial match in 1926 and beyond.

Ross Biddiscombe is the author of Ryder Cup Revealed: Tales of the Unexpected and will be posting regularly on Substack about the history of the match and other Ryder Cup connections.